Hello! My name is Alison Mahoney. I’m a PhD candidate in Theatre and Performance Studies at Pitt, where I’m working on my dissertation, which focuses on the work of disability performance collectives, especially those whose performances have contested or nonnormative relationships to speech and voice. This summer, I received funding from various PittGlobal scholarships and grants to conduct ethnographic and archival research in London for two chapters of my dissertation. I’m very grateful to the International Studies Fund, European Studies Center, the Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Program (NRIEP), and the Women’s International Club for funding my research, and I’m glad to be able to share some of my project with you here!

While based in London for four weeks in June and July, I attended performances by and conducted interviews with Drag Syndrome, a troupe of drag performers who have Down syndrome, and visited the London Metropolitan Archives and the National Disability Arts Collection and Archives (NDACA) to research the historical context of the disability arts movement in the United Kingdom. To start, I’ll briefly explain my dissertation project overall, and then share a bit about the ethnographic and archival research I conducted this summer.

My dissertation, “Nonspeaking: Performances of Crip Collectivity,” considers several examples of what I term “nonspeaking performance” that highlight the relational nature of crip ensemble performance. I argue that nonspeaking is an undertheorized and critical aspect of disability performance that contributes to crip performance aesthetics and relational disability politics. Longstanding culturally ingrained connections between voice and individual agency can and often do foreclose understandings of nonspeaking subjects as political actors. Access to authoritative and individually-authored speech that follows linguistic norms is often a prerequisite for, or a primary goal of, cultural participation. I therefore pose several case studies in which subjects’ access to speech is limited or communicated atypically for a variety of reasons: archival absence, intellectual disability, presumed incompetence, physical or vocal absence due to illness, or combinations of these factors. In examining performances by subjects with contested and/or unreliable relationships to speech, I decenter the role of individual voice as essential to personhood, arguing instead that these performance collectives and collaborations refigure agency as a collective quality. My dissertation uses archival research alongside ethnographic analysis to understand how disability culture and performances of nonspeaking relate to and shape transatlantic exchange among political movements in the United States and United Kingdom.

Drag Syndrome

I have been interested in (okay…a little obsessed with) Drag Syndrome’s work for several years. I first heard about them through social media, where they have a very active presence on Instagram and TikTok. During the early months of the Covid pandemic in 2020, I joined them for several Zoom performances and had the opportunity to interview their artistic director, Daniel Vais. I knew that I wanted to write about their work for my dissertation because of the way their performances challenge drag conventions through their sporadic use of lip syncing, collaborative performance, and their incorporation of messiness and childishness into their looks.

I joined Drag Syndrome for their performances on the London Pride mainstage in Trafalgar Square, for a small café pop-up called “Toasted Love” at a small venue called the Hornecker Centre, and for a tour up north to Mansfield for OneFest, a celebration of neurodiversity. Seeing the group perform in these three very different venues was incredibly informative. London Pride was a very mainstream queer event with thousands of people in attendance, at which Drag Syndrome were some of the only disabled performers. The Hornecker Centre, on the other hand, was tiny: just a small room covered floor to ceiling in eclectic and provocative queer art, where Drag Syndrome felt very much at home. Whereas the focus at both pride and the Hornecker Centre was on queer performance, OneFest really centered Drag Syndrome’s disability narrative, including them as leaders of a “March for More” to advocate for greater social inclusion for learning disabled communities in the UK. Of course, the boundaries between disability advocacy, the queer underground, and mainstream queer spaces are far more porous than I might seem to suggest here, and there were aspects of each of these scenes in all three venues. That said, I learned a lot from seeing the different audiences’ responses to Drag Syndrome and the way the ensemble engaged with other artists booked at these venues.

I was lucky to be able to spend time with the artists beyond just seeing them perform, and I conducted both formal and informal interviews with them about their careers, their thoughts about drag as an art form, and the widely varied responses to their performances on social media. Beyond just speaking with the artists, I danced with them, sang along to pop songs with them, and shared meals with them (they make a mean toastie). Because my research is rooted in performance studies, these kinds of interactions are equally (if not more) important to me as more traditional interviews. Spending this kind of unstructured (and very fun) time with Drag Syndrome gave me a much clearer sense of the troupe’s dynamics and contributions to drag as an art form than I ever would have gotten through just seeing their videos online and speaking with them over Zoom.

Visiting the Archives

I have long been interested in the availability of public funding for arts and disability (and disability arts) in the United Kingdom that allows more experimental art practices (like Drag Syndrome’s) to thrive. I was excited to spend time at the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive (NDACA) reading through the records of early disability arts organizations who advocated for greater availability of such funding and seeing through these records the ways access to funding from the Arts Council impacted their growth. As this funding faces further and further cuts, it was especially interesting to research the strategies individual disabled artists and arts companies used to advocate for their work.

I have long been interested in the availability of public funding for arts and disability (and disability arts) in the United Kingdom that allows more experimental art practices (like Drag Syndrome’s) to thrive. I was excited to spend time at the National Disability Arts Collection and Archive (NDACA) reading through the records of early disability arts organizations who advocated for greater availability of such funding and seeing through these records the ways access to funding from the Arts Council impacted their growth. As this funding faces further and further cuts, it was especially interesting to research the strategies individual disabled artists and arts companies used to advocate for their work.

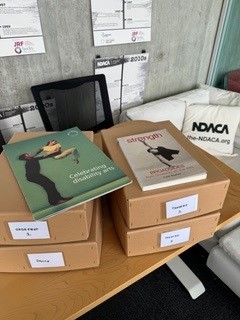

NDACA was an especially striking archive for several reasons that go beyond the boxes’ contents. The archive is relatively new, and I was impressed by how cozy the reading room was. It was clearly designed to accommodate disabled researchers, with lots of cushioning, different types of chairs, and options for engaging digitally or physically. Photos in the digital archive have meticulously written alt-text for those who use screen readers; this care for accessibility is also part of why the archive has not yet been fully catalogued. (Though I’m excited for the day they finish cataloguing all of their amazing materials, I loved getting to sift through unsorted boxes of ephemera.) Visiting an archive with such an emphasis on accessibility and disability justice was a unique experience I’ll never forget.

My time in London this summer was incredibly generative, and I’m very much looking forward to going back as soon as I can. In the meantime, I’m excited to get writing! Many thanks again to the International Studies Fund, European Studies Center, Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Program, and the Women’s International Club for making this research possible.